Living Kitchen explores our relationship with objects in a world of programmable matter.

As a kid I used to spend countless afternoons playing video games with my brothers. Back in the early nineties, the low-resolution graphics of the games created a unique visual language — a digital language — in which each pixel on screen could rearrange to tell a new story. I remember when I was about 4 years old, I was standing on a chair and looking intensively at a painting hanging on the kitchen wall. No matter how close I got to the painting, I still couldn’t see any pixels. “The world is made of atoms, not pixels,” said my mum as she saw me, nose glued on the art piece.

She was right; our everyday objects are made of atoms, and we can’t rearrange atoms the way we can program pixels.

A Swarm of Tiny Robots

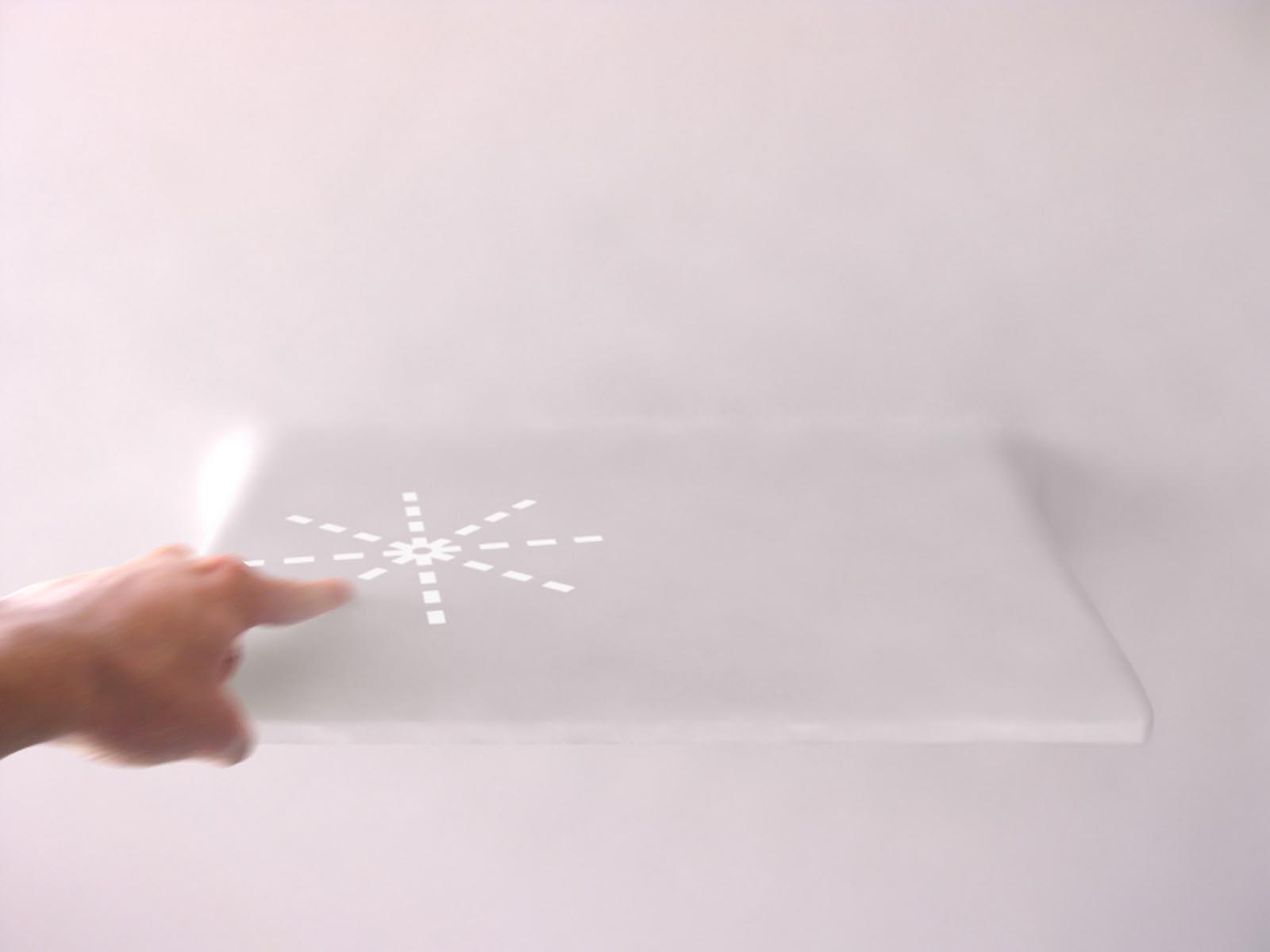

Fast forward 20 years. In Pittsburg, a group of computer scientists at Carnegie Mellon University are developing what they coined "claytronics". It is a programmable matter that holds the potential of revolutionizing our relationship with objects and architecture. Tiny intelligent robots, the size of a human hair, use electrostatics to stick together, communicate, and change their position in space. By introducing programming into these robots, or "catoms" — short for claytronic atoms — they’re able to form new shapes by reacting to external stimuli, like a blob of Play-Doh with a soul.

Matter as Software

This is huge. So far we’ve experienced objects in two distinct ways, physically and digitally. A smartphone for instance is experienced via its industrial design and software design. Both aspects have their unique properties. The physical object is static and tangible, whereas software is dynamic and intangible. With claytronics those qualities overlap, and physical matter gains digital properties. The shape of a phone could be programmed to morph and better fit the experience of each app. Opening Youtube for example could increase a phone’s screen size and provide an ideal viewing experience.

On a bigger scale, buildings and bridges could self-repair in critical situations. Clothing could change its design and thermal properties in tune with the weather. Prosthetic arms and legs could transform to support people’s needs. Only our imagination holds us back from imagining the possibilities.

Form follows Flow

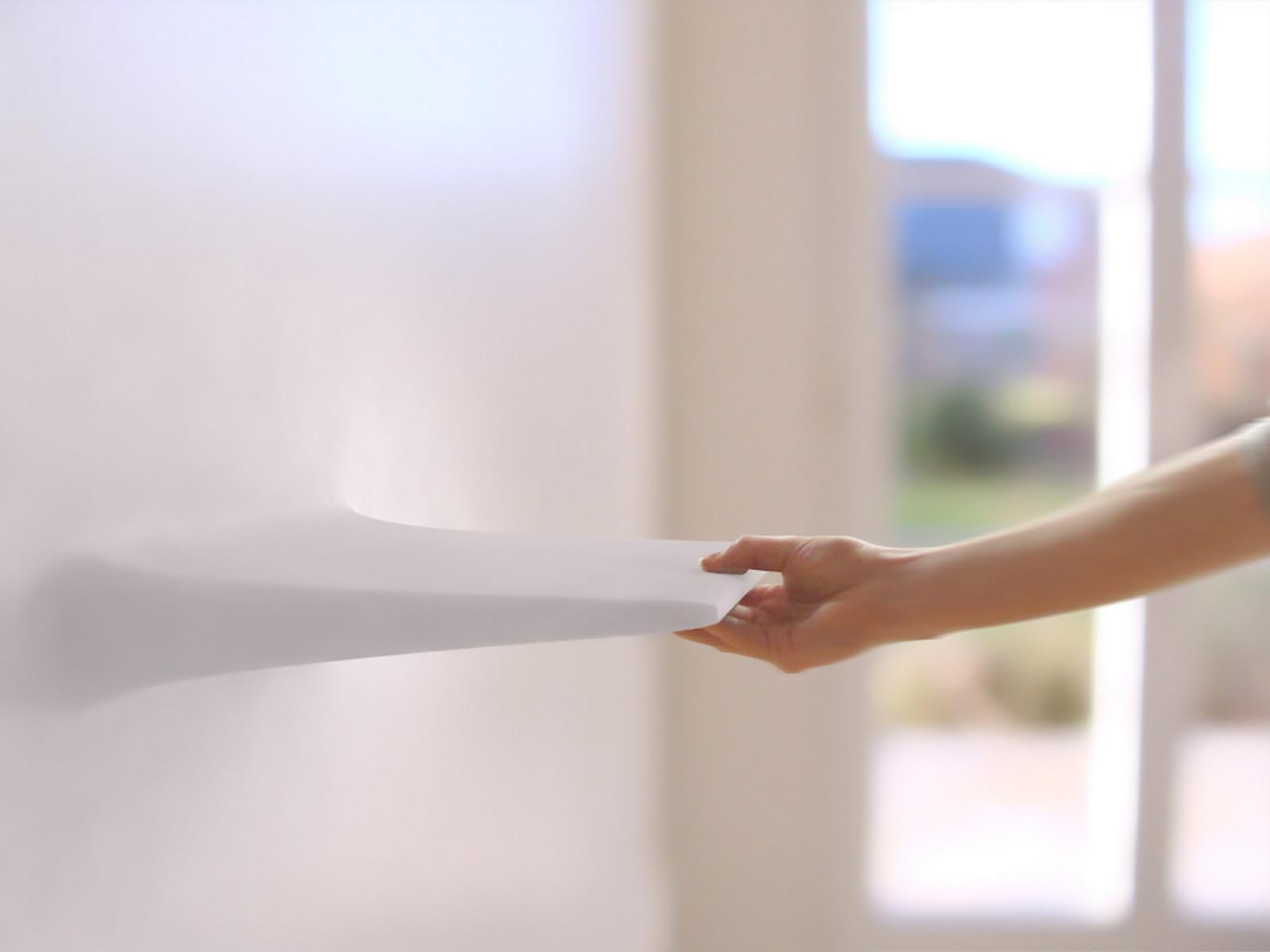

This is as much of a technological revolution as it is a behavioral one. If any object can transform into any other object, this establishes a radically new status quo on how we manipulate the world around us. Objects would no longer dictate a function by the way they’re shaped. Instead, their shapes would adapt depending on what we need. This will bring a whole new set of opportunities for a hybrid generation of industrial/interaction designers, who will have to consider an object's constant dynamicity and relationship to context.

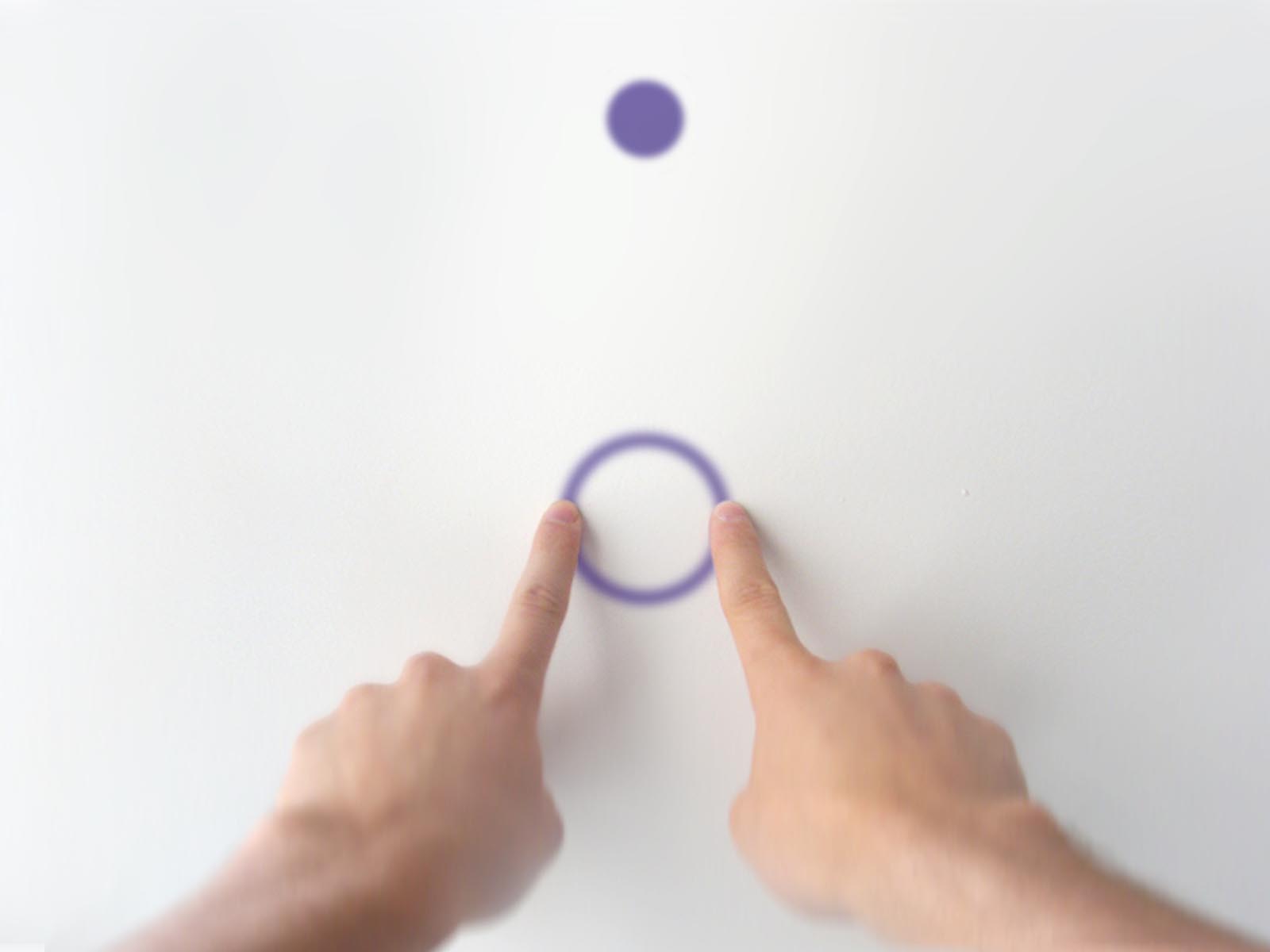

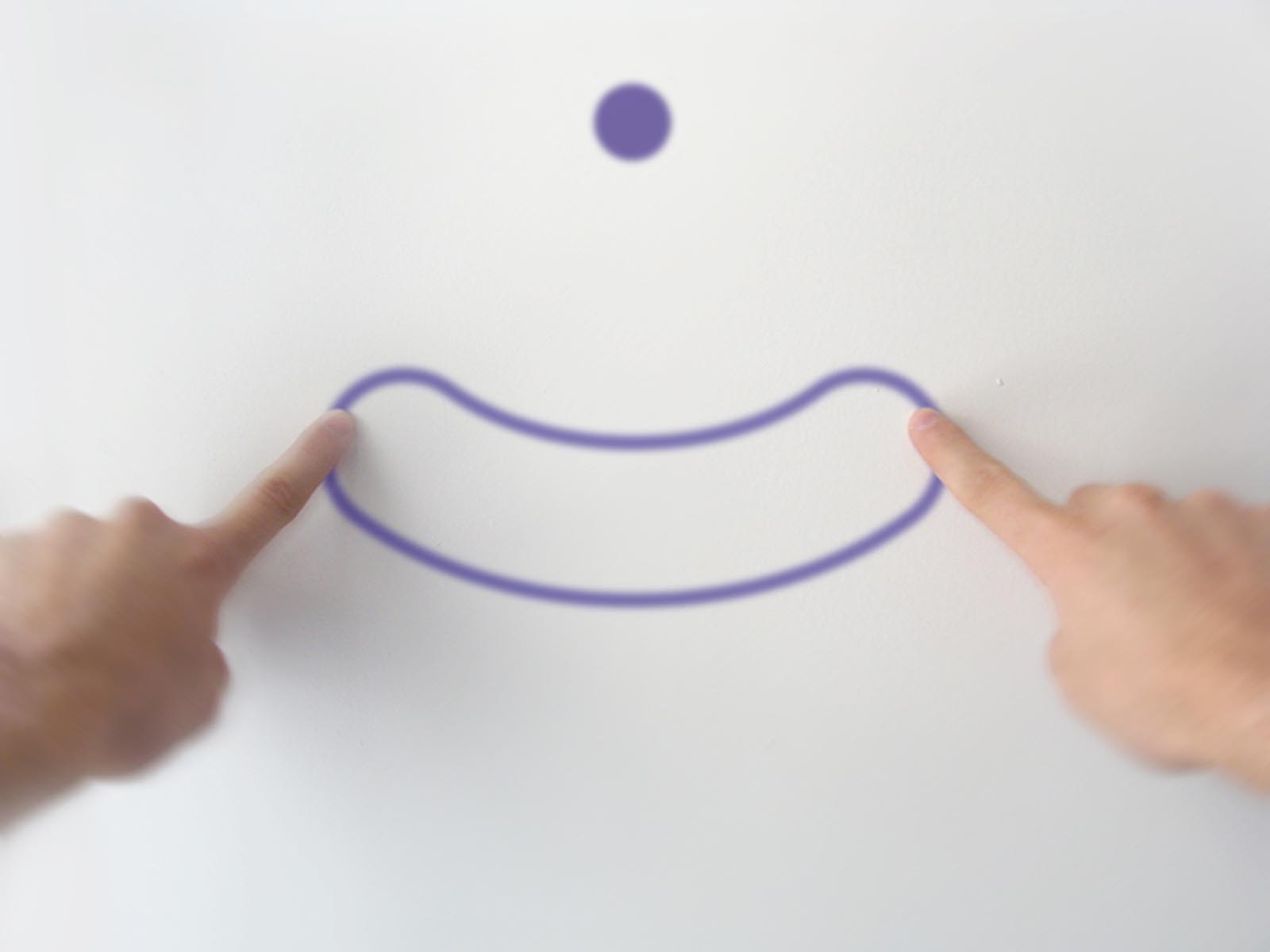

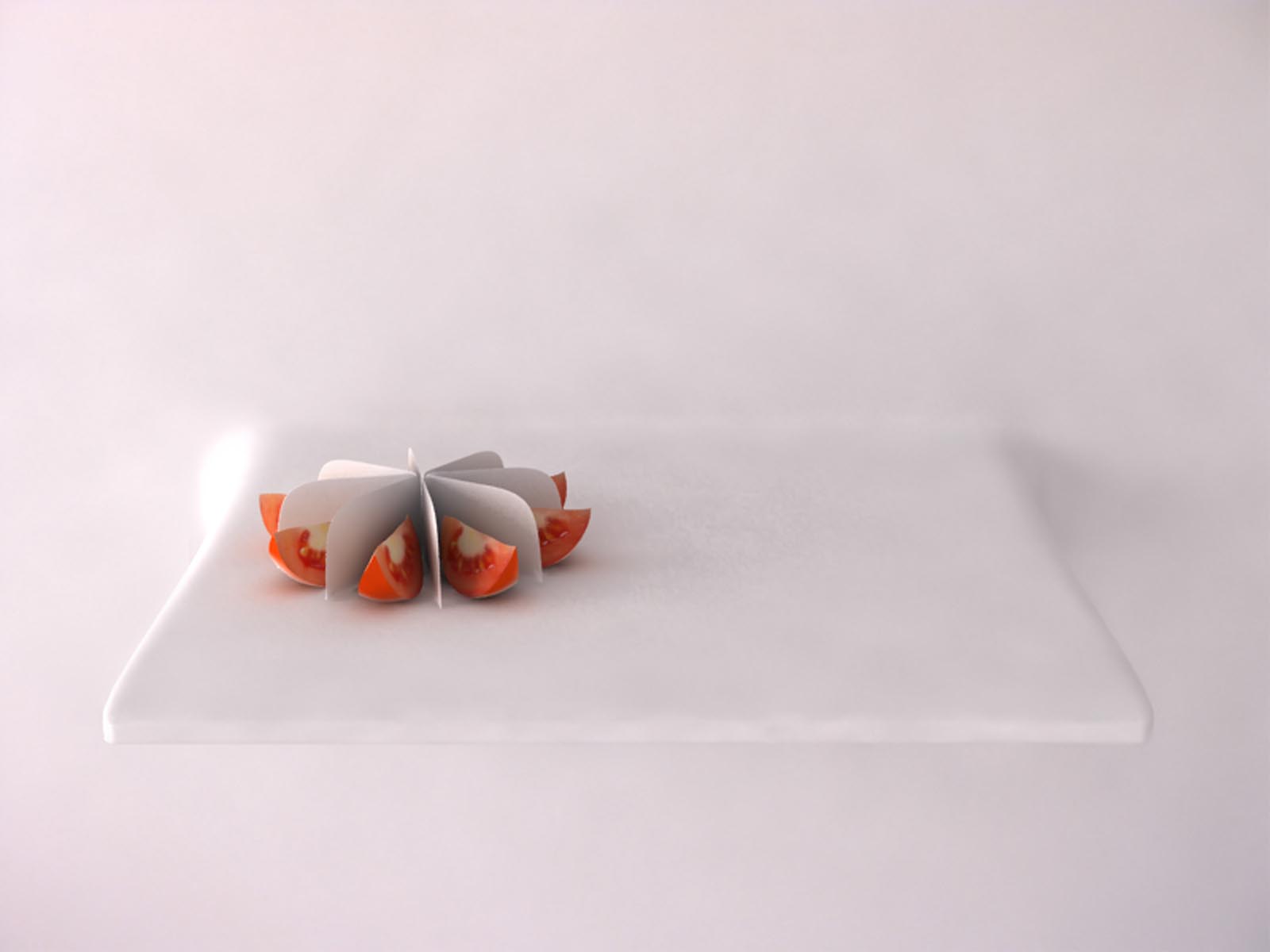

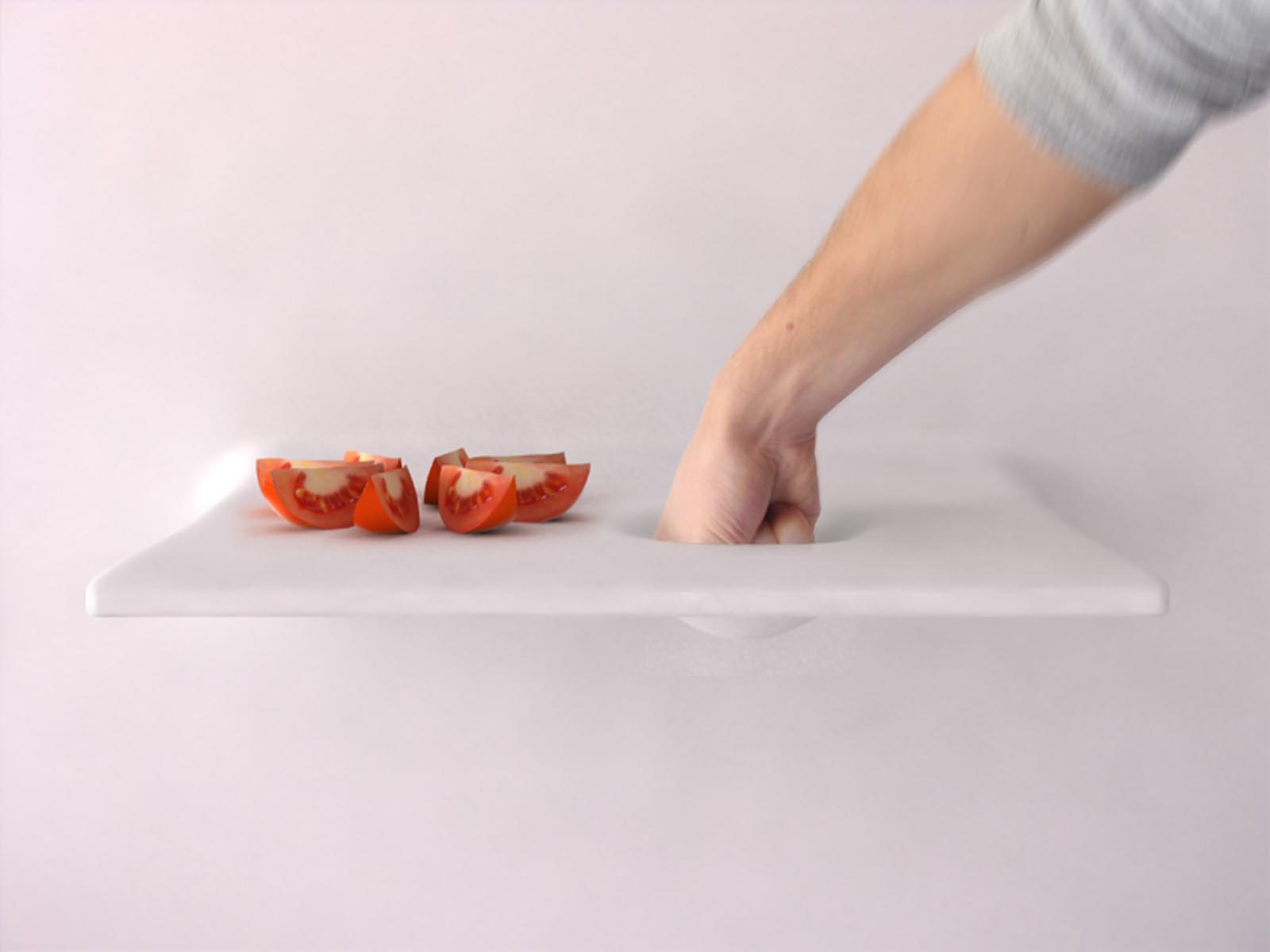

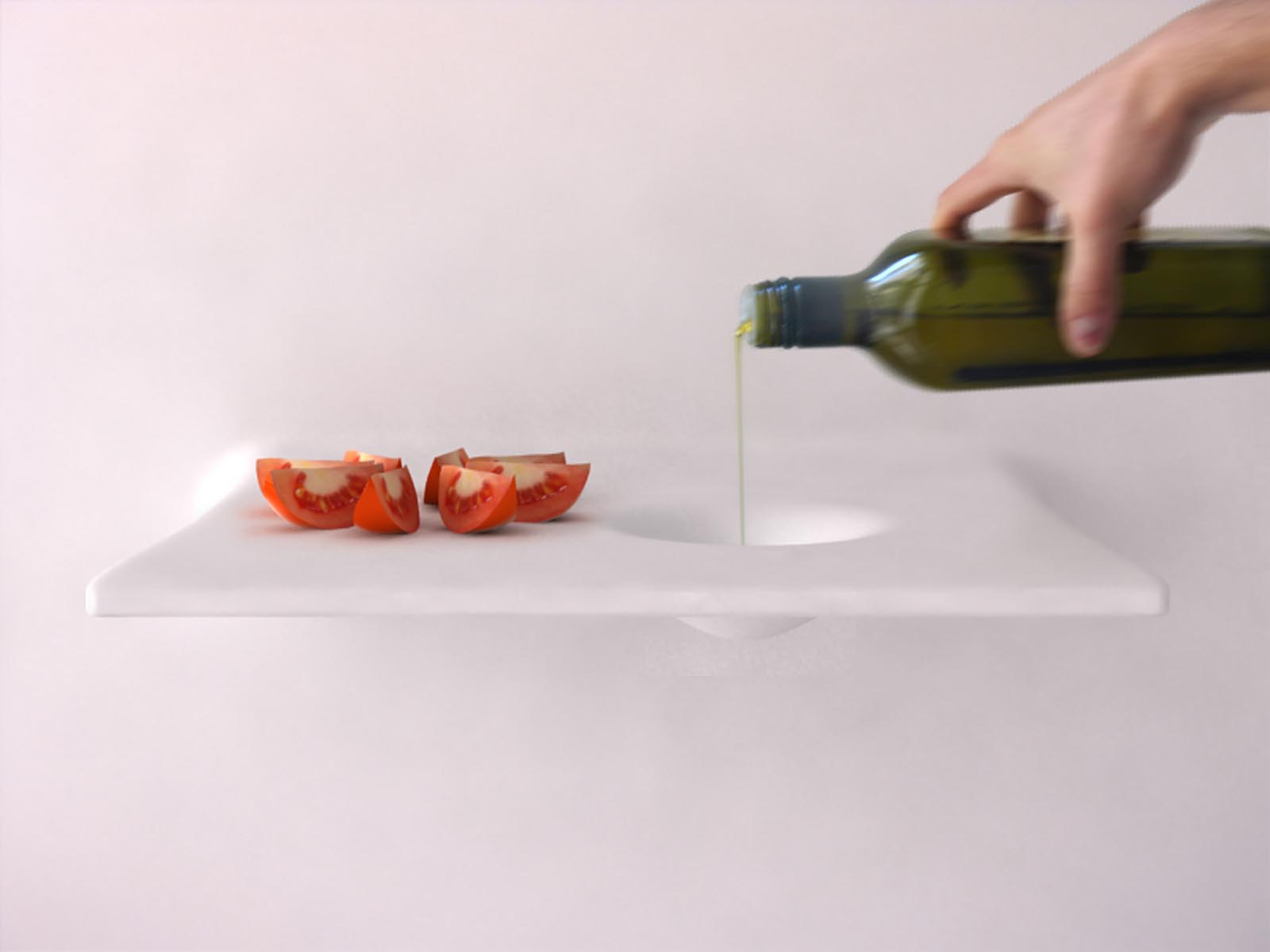

With Living Kitchen I wanted to explore how people would interact within this environment. The matter being reactive to external stimuli, people could make faucets, sinks, or cutting-boards appear just by tapping the surface. The volumes could be stretched, twisted, and bend by users to match their needs. Users could even download shapes from crowdsourced libraries.

Sparking the Conversation

The foundation of this shape-shifting matter is evolving quickly and scientists are working hard on bringing programmable matter to life. "Getting the robots to compute, and as a result self-assemble, changing the overall structure's physical properties, is the next step," says Goldstein, a computer scientists at Carnegie Mellon.

With this project I wanted to bring awareness to this nascent technology. Although concepts like Living Kitchen are design fictions today, we should start the conversation on what scenarios and applications will be desirable tomorrow.

What would you do with programmable matter?